c But as the hours tick by and fuel remains elusive, a different kind of market springs to life just around the corner. There, along less-travelled alleys, unofficial petrol vendors set up shop, offering fuel at prices well above the official rate. For many, this black market fuel becomes a necessary alternative to the long queues and unpredictable availability of official supply.

The current fuel scarcity in Nigeria is transforming the black market (or more formally the underground or shadow economy) into an alternative for accessing fuel. This, much like the surge of the Point of Sale (POS) terminals that have become preponderant during the cash scarcity crisis, is morphing into “a more reliable” source of getting fuel during the fuel scarcity debacle.

Read also: Black market booms as petrol stations go nocturnal, shut out motorists

The rise of POS (point-of-sale) terminals in Nigeria marks a significant transformation in the country's banking sector, addressing gaps left by the uneven distribution of ATMs and bank branches. Driven by the need for greater accessibility and convenience, POS terminals have proliferated, especially in rural and underserved areas. This growth has been supported by regulatory initiatives aimed at enhancing financial inclusion, providing a practical solution for transactions and financial services where traditional banking infrastructure is lacking.

In parallel, Nigeria's petrol black market has emerged as a response to persistent fuel shortages and inefficiencies in the formal distribution system. Price controls and subsidy policies have created discrepancies between regulated fuel prices and actual market demand, fostering the growth of illicit trading. Unlike POS terminals, which operate within a legal framework, the black market for petrol is informal and unregulated, highlighting how deficiencies in official systems can lead to alternative, albeit unregulated, market solutions. The comparison between these two phenomena sheds light on the broader impact of informal markets and offers insights into potential strategies for addressing similar challenges.

This underground economy is driven by allegations that some filling stations deliberately withhold fuel during regular hours, only to sell it at inflated prices to black marketers at night.

“Unlike POS terminals, which operate within a legal framework, the black market for petrol is informal and unregulated, highlighting how deficiencies in official systems can lead to alternative, albeit unregulated, market solutions.”

As a result, motorists, unable to access fuel through formal channels, turn to these informal networks, paying exorbitant prices just to keep their vehicles running. This trend reflects a broader issue of systemic inefficiency and governance failures, where the population is left to navigate a landscape of scarcity through informal means.

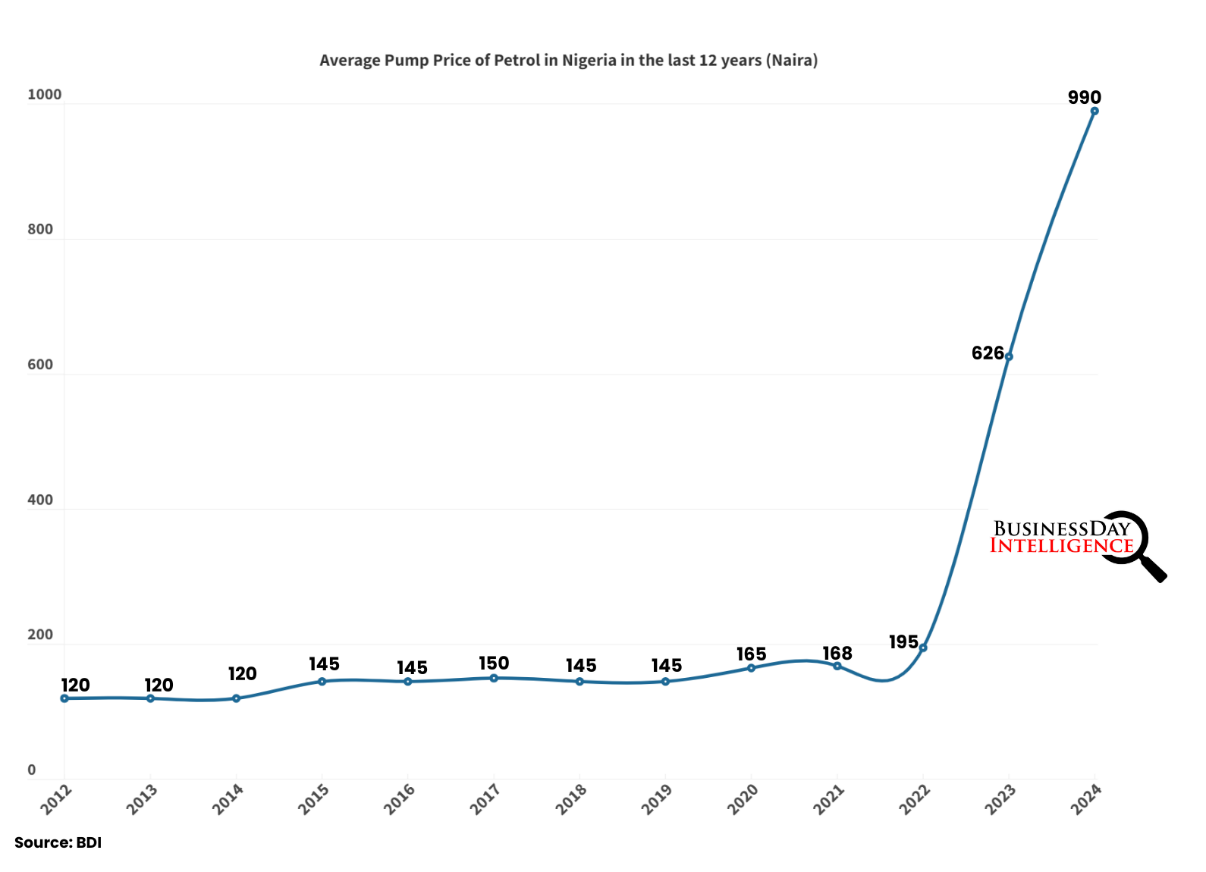

Trajectory of Nigeria’s Petrol Price Watch

Nigeria—for the umpteenth time this year—is in the grip of a severe fuel scarcity, and as official supply chains falter, the black market for petrol is thriving. With petrol selling for as much as ₦1000 at the pumps across some states and ₦1,200-₦2000 per litre on the black market, the situation has left many Nigerians feeling cornered and frustrated. The formal channels have been severely hindered, owing largely to logistical bottlenecks, subsidy removal, and foreign exchange constraints. Nigerians are now increasingly forced to rely on informal channels to meet their basic needs.

In July 2024, Nigeria experienced a significant increase in retail petrol prices, with Katsina emerging as the most expensive state, reaching N950.00 per litre compared to N604.55 in July 2023. Similarly, Jigawa and Benue saw substantial price hikes, climbing from N625.80 and N537.00 to N903.08 and N846.95, respectively. This broader trend of rising petrol costs reflects underlying market dynamics and economic factors impacting fuel prices across the country.

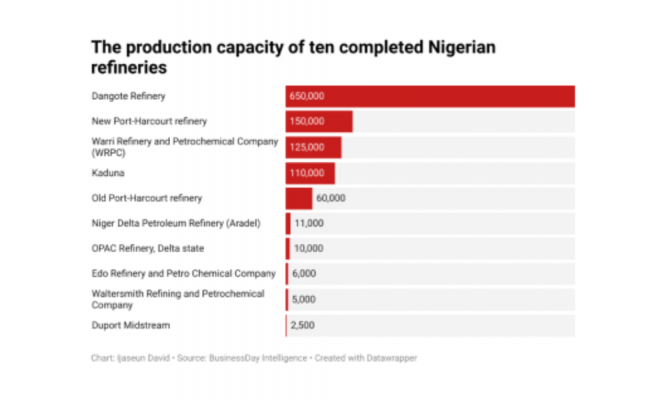

Read also: FG eyes increased petrol output from Dangote, Port-Harcourt refineries by November

Month-on-month data shows a smaller but noticeable increase, with average petrol prices rising by 2.72 percent from N750.17 in June to N770.54 in July. The North-West Zone reported the highest average petrol price at N820.10, while the South-South Zone had the lowest at N678.30. This regional disparity underscores the uneven distribution of gasoline costs and highlights the broader trend of increasing fuel prices nationwide.

Comparative Analysis: PoS versus Black Market

The normalisation of the black market as a solution to fuel scarcity mirrors the role of POS terminals during the cash crunch, underscoring the deepening socio-economic challenges facing Nigerians.

POS terminals and the petrol black market both arose as pragmatic responses to gaps in formal service channels, addressing unmet demand in their respective sectors. POS terminals emerged to fill the void left by insufficient ATM and banking infrastructure, particularly in remote and underserved areas. Similarly, the petrol black market developed in response to frequent fuel shortages and distribution inefficiencies in Nigeria's formal fuel sector. Both phenomena illustrate how informal solutions can arise when formal systems fail to adequately meet consumer needs.

The convenience and accessibility offered by both POS terminals and the petrol black market play a crucial role in their widespread adoption. POS terminals provide a more immediate and flexible alternative for financial transactions, particularly in areas where traditional banking services are sparse. Similarly, the petrol black market offers a more reliable and readily available source of fuel for consumers facing long queues or shortages at official petrol stations. In both cases, these informal markets fill critical gaps, offering consumers access to essential services where formal channels fall short.

Economic incentives drive the growth of both POS terminals and the petrol black market, fuelling their expansion. For POS terminals, the profitability of transaction fees and commissions motivates entrepreneurs to set up terminals in underserved areas, where they can capture a significant share of the market. In the petrol black market, arbitrageurs profit from the disparity between regulated fuel prices and market demand, often selling fuel at higher prices to capitalise on shortages. This profit-driven expansion underscores the powerful economic forces at play in both informal markets, as they exploit deficiencies in formal systems to generate substantial financial returns.

As fuel scarcity grips Nigeria, the black market for petrol is booming. For the past two weeks, major cities like Abuja and Lagos have seen motorists spending hours in long queues at increasingly scarce filling stations. With many stations shutting their doors during the day, frustrated consumers are turning to the black market, where prices have surged to as high as N1,200 per litre. “I’ve been here since 5 a.m., and it’s already noon,” said Bayo, a Lagos resident. “If this continues, I might have to buy from the black market, but the prices are killing us.” Another motorist, Aisha, voiced her frustration, saying, “How can fuel be so expensive in a country like Nigeria? It’s like the government doesn’t care about us.” Similarly, Emeka, a frequent traveller, lamented, “It’s unbelievable. We’re forced to pay outrageous prices just to get to work.”

The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) has acknowledged the severity of the crisis, attributing the shortage to logistical challenges in evacuating fuel from vessels. Olufemi Soneye, the NNPC’s chief corporate communications officer, assured that the company is addressing these challenges and expects an improvement by mid-week. “The NNPC Ltd regrets the tightness in fuel supply and urges motorists to shun panic buying,” Soneye said. “We are working round the clock to restore normalcy.” Despite these reassurances, many Nigerians remain sceptical. “They keep promising, but the queues and prices never change,” said Fola, a resident of Abuja. “It feels like they’re just buying time.”

Read also: Tinubu’s petrol subsidy gulps N15trn as scarcity worsens

The economic impact of fuel scarcity is profound. Increased transportation costs are driving up prices for goods and services, exacerbating the financial strain on Nigerians already grappling with high inflation and unemployment. Chike, a small business owner in Lagos, explained, “When transport costs go up, everything else does too. I have to pass these costs onto my customers, and everyone is suffering.” The situation is further complicated by the dangers of black market gasoline, which is often stored in unsafe conditions and can be adulterated, causing damage to vehicles. Amina, a Lagos resident, highlighted the risks, saying, “We live in fear every day. Petrol stored in jerry cans could easily cause a fire.” Uche, a black-market seller, defended his actions, stating, “This is how I feed my family. The government needs to fix the system so we don’t have to do this.” Meanwhile, Nnamdi, a mechanic, added, “Adulterated fuel ruins engines and costs us more in repairs. It’s a never-ending cycle of trouble.”

In sum, while black market arbitrageurs in the Nigerian petrol market can be temporarily sustainable, especially in times of market inefficiencies and shortages, their long-term viability is questionable. Unlike the sustained growth of agency banking, which was integrated into the formal economy, black market petrol trading is likely to face greater challenges, particularly from regulatory pressures and potential improvements in the formal fuel distribution system.

Chiamaka is a junior research and data analyst at BusinessDay Intelligence. She has a degree in Economics with over one year of cognate experience in data visualisation and handling.

For Enquiries: Nike Alao-Chief Research Officer: +2348034856676