Nigeria has accumulated a large stock of dead assets estimated at N180 trillion, yet the nation is foot-dragging to unlock them even as public debt piles up.

Dead assets are not generating income and do not increase productivity or wealth. In a book entitled ‘The Mystery of Capital,’ Hernando de Soto, a Spanish explorer and conquistador, explains that dead capital holds the potential for significant economic growth for nations with economic challenges.

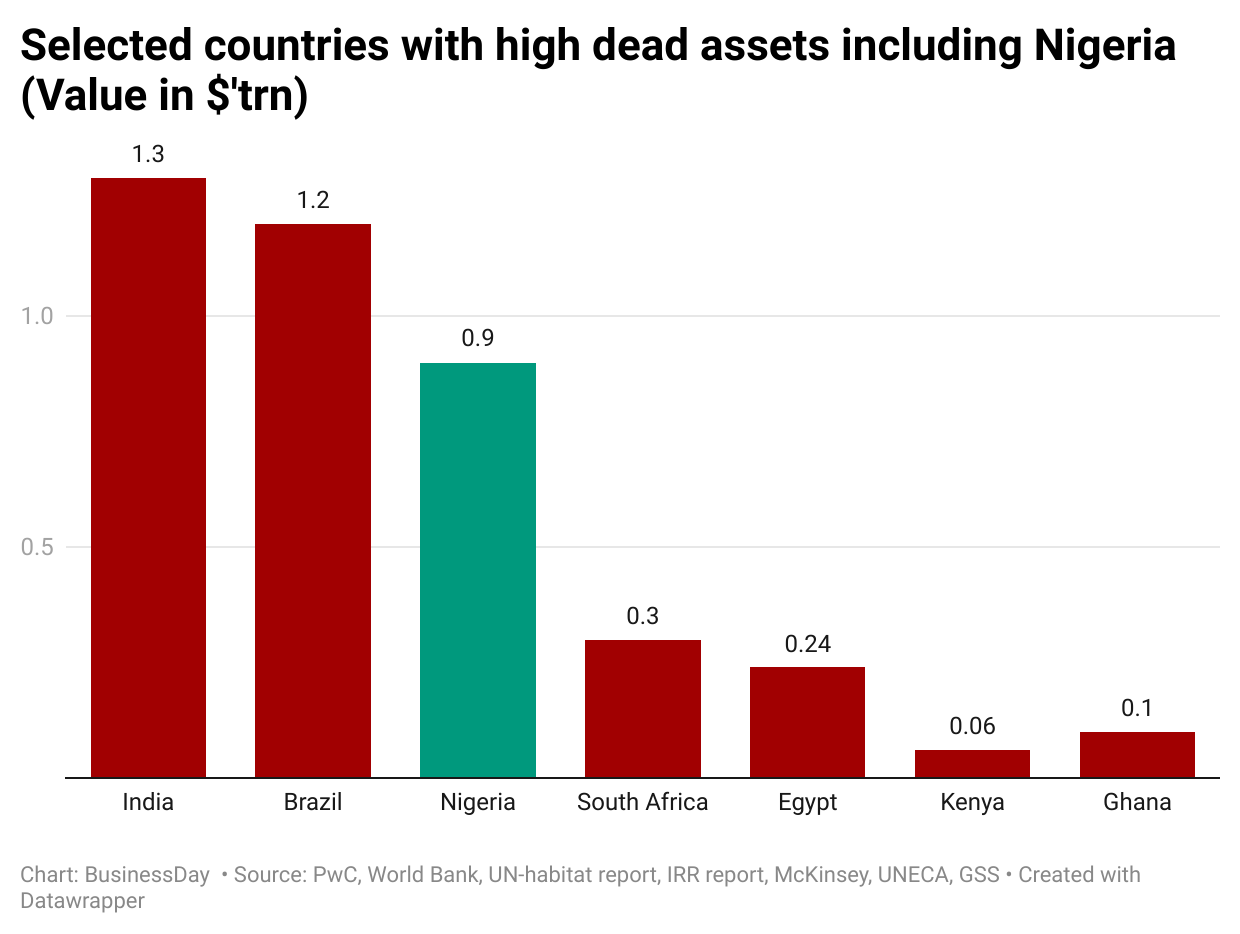

According to PwC’s estimates, Nigeria has as much as N180 trillion or $900 billion trapped in dead assets, mostly in real estate. Unlocking the capital could be a game changer for a cash-strapped nation with a debt service to revenue ratio of 74 percent in the first quarter (Q1) of 2024.

Nigeria's public debt has risen from N12.6 trillion in 2015 to N121.7 trillion in 2024, according to data from the Debt Management Office (DMO).

Meanwhile, the country sits on vast dead assets, including abandoned government properties, dormant state-owned enterprises, and unutilised land.

Chudi Ubosi, principal partner at Ubosi Eleh + Co, noted that the country has over 300 real estate properties worldwide, many of which are abandoned and underutilised while thousands of kilometres of road projects at various stages of construction have also been abandoned nationwide.

Read also: Nigeria steps up bid to unlock N180trn dead assets

Efforts to unlock assets not working

Nigerian government has, over the years, launched various initiatives aimed at converting these dead assets into productive resources. One such initiative was the Presidential Initiative on Infrastructure, which sought to lease out abandoned government properties to private investors. However, it did not work due to systemic challenges.

“One of the primary reasons Nigeria has struggled to unlock its dead assets is bureaucracy,” said Ayobami Ishola, a US-based finance expert with a leading international research firm.

Ishola identified lengthy approval processes, inconsistent government policies, and a lack of inter-agency coordination as parts of the bottlenecks hindering the country's progress in its efforts to revitalise dead assets.

A report by the Nigeria Economic Summit Group (NESG) highlighted that over 80 percent of government-owned properties in Abuja and Lagos remains unoccupied, yet transferring ownership or usage rights involves navigating a complex web of red-tape.

Corruption has also played a significant role in stalling efforts to convert dead assets into productive use. Cases of public officials exploiting legal loopholes to maintain control over these assets have been documented, reducing transparency and accountability.

The Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC) reported that up to 25 percent of identified dead assets have been embroiled in corruption-related disputes, preventing their productive utilisation.

The impact of this failure is evident. Nigeria's annual debt servicing costs have risen to over $10 billion, taking over 70 percent of government revenue.

This unproductive use of assets means lost opportunities for job creation, creating homes to bridge the country’s estimated 28 million housing units deficit, economic growth, and infrastructural development.

Ajaokuta Steel Plant, NIOMCO nearly dead

Incorporated in 1979, the Ajaokuta Steel Plant (ASP), estimated at more than $8 billion, is one out of many assets owned by Nigeris, having reached a 98 percent completion as at 1994. However, it has remained dormant—a huge economic waste.

ASP has a gigantic structure with a 68 km road network plus 24 housing estates. Some of the estates have over 1,000 homes, a seaport, and a 110-megawatt power generation plant.

There are 43 separate plants in Ajaokuta alone. It is estimated that if Ajaokuta becomes operational after 45 years of near-completion, it will create, at least, 500,000 jobs.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) reported that the country currently imports steel, aluminium products and associated derivatives of approximately 25 metric tonnes per annum estimated at $4.5 billion.

“Ajaokuta is Nigeria and probably Africa's biggest failure. It has failed. Can it be made to work? Yes. But the cost to integrate Ajaokuta with her mines and rails can be used to build new smaller modern turnkey functional steel mills,” said Kalu Aja, a US-based financial expert in a post on X (formerly Twitter).

“The government should get out of Ajaokuta, sell the place and allow private sector capital and expertise to restructure and own it,” he added.

Read also: Sell off dead assets to raise funds, Aigbogun tells Tinubu

The N40bn Federal Secretariat Complex, Ikoyi

Built in 1976 for federal civil servants, the 12-floor federal secretariat in Ikoyi, Lagos has been abandoned since 1991 when the federal capital was moved from Lagos to Abuja by then military president, Ibrahim Babangida.

Though the massive secretariat complex was among the many federal government properties sold out to private buyers by the Olusegun Obasanjo administration between 2002 and 2006, the complex is yet to be put into use due to bureaucratic red-tape and vested interests.

An estate surveyor and valuer, who has done a valuation job on the complex, revealed to BusinessDay that the value of that asset, including the land and the physical structure, is about N40 billion, adding that it could have been more if the asset had been in use, especially with its prime location.

Maryanne Udo Okonjo, CEO, Fine and Country International, wants the complex and other wasting national monuments to be transformed into other uses as it is done in other countries of the world.

She cited St Pancreas Renaissance Hotel in the UK, a hotel facility that was abandoned for 69 years before it was transformed in 2011 into a five-star hotel.

Over $25bn spent on fixing NNPC refineries

Nigeria has four state-owned decrepit refineries with a combined 4450,000 barrels per day production capacity: 110,000 barrels Kaduna plant in the north and three units in the oil-rich Niger Delta, including the 125,000 barrels Warri refinery.

But these refineries, despite over $25 billion spent on reviving them, have hardly produced any gasoline, worsening Nigeria's reliance on fuel imports despite being Africa's largest oil producer.

Hope of producing gasoline came alive when the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) started a $1.5 billion rehabilitation for Port Harcourt refinery. But, till date, the story remains the same: it's yet to begin operations.

Analysts have suggested privatisation or public private partnerships as ways of bringing the moribund refineries to life as this will boost the economy, reduce foreign exchange outflows and create employment opportunities.

“Instead of selling off the refineries to private investors, why not just address the issues of corruption and inefficiencies that have historically plagued the multi-billion projects,” said Fola Ajayi, a Lagos-based energy expert.

Tinapa: Nigeria's $450m business & leisure resort lost in the shadow

Located in oil-rich Cross River State, Tinapa, with its futuristic film studios, luxury shops, elevated light railway and a free trade zone, should be a veritable source of revenue for tourism enthusiasts, a commercial hub for West Africa raking in millions of dollars.

But 10 years after it opened, the 80,000 square metres (861,000 square feet) of warehouses and shops, estimated to cost $450 million (413 million euros) to build in the Niger-Delta, is a ghost town and has become a symbol of monumental waste.

Opened in 2007 with the aim to attract Nigerian millionaires, who ordinarily jetted off to Dubai or London for shopping, as well as make Cross River a commercial crossroads on the Atlantic coast, has become a financial black hole for its backers.

“At that time, everyone was excited. Tinapa was going to boost economic development of the whole region and create thousands of jobs,” Bassey Ndem, who was in charge of the project, was quoted as saying.

He added, “Everything was going well at first. At the peak, in 2009, we generated $30 million of revenue. But we faced a lot of resistance from the Customs. They really didn’t want the tax-free zone to work.”

Nonso Obikili, an economist and policy expert, said Tinapa’s downfall was largely due to lack of existing infrastructure to transport goods: bad roads and an average-sized port.

“It was a wide project conceived with the deep-sea port, which was supposed to enable big ships to come to Calabar,” he said.